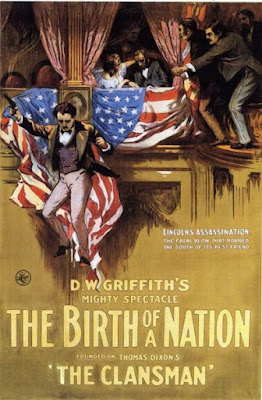

The Birth of a Nation (also known as The Clansman) is one of the most influential and controversial films in the history of American cinema. Set during the American Civil War and directed by D.W. Griffith, the film was released on February 8, 1915. It is important in film history for its innovative technical achievements, for its narrative style constructed classic film language, and also for its controversial promotion of white supremacism and glorification of the Ku Klux Klan.

The Birth of a Nation is based on Thomas Dixon's The Clansman, a novel and play that heroically portrays the Ku Klux Klan. The KKK describes itself, even today, as "the invisible empire" and "the invisible nation" protecting "white womanhood". Thus, some have interpreted the title as referring to "The Birth of the Invisible Nation." Officially, however, the title means that the United States was not truly a nation until after the Civil War reunited the North and South, as symbolized in the film by the Stoneman-Cameron marriages.

Director David Wark Griffith.

Synopsis

The film was originally presented in two parts separated by an intermission. Part 1 depicts pre-Civil War America, introducing two juxtaposed families: the Northern Stonemans, consisting of abolitionist Congressman Austin Stoneman (based on real-life Reconstruction-era Congressman Thaddeus Stevens), his two sons, and his daughter, Elsie, and the Southern Camerons, a family including two daughters (Margaret and Flora) and three sons, most notably Ben.

The film was originally presented in two parts separated by an intermission. Part 1 depicts pre-Civil War America, introducing two juxtaposed families: the Northern Stonemans, consisting of abolitionist Congressman Austin Stoneman (based on real-life Reconstruction-era Congressman Thaddeus Stevens), his two sons, and his daughter, Elsie, and the Southern Camerons, a family including two daughters (Margaret and Flora) and three sons, most notably Ben.The Stoneman boys visit the Camerons at their South Carolina estate, a pinnacle of the Old South, and all it represents. The eldest Stoneman boy falls in love with Margaret Cameron, and Ben Cameron idolizes a picture of Elsie Stoneman. When the Civil War begins, all of the boys join their respective armies. A black militia (with a white leader) ransacks the Cameron house, attempting to rape all the Cameron women, who are rescued when Confederate soldiers rout the militia. Meanwhile, the youngest Stoneman and two Cameron boys are killed in the war. Ben Cameron is wounded after a heroic battle in which he gains the nickname, "the Little Colonel," by which he is referred to for the rest of the film.  The Little Colonel is taken to a Northern hospital where he meets Elsie, who is working there as a nurse. The war ends and Abraham Lincoln is assassinated at Ford's Theater, allowing Austin Stoneman and other radical congressmen to "punish" the South for secession with Reconstruction.

The Little Colonel is taken to a Northern hospital where he meets Elsie, who is working there as a nurse. The war ends and Abraham Lincoln is assassinated at Ford's Theater, allowing Austin Stoneman and other radical congressmen to "punish" the South for secession with Reconstruction.

The Little Colonel is taken to a Northern hospital where he meets Elsie, who is working there as a nurse. The war ends and Abraham Lincoln is assassinated at Ford's Theater, allowing Austin Stoneman and other radical congressmen to "punish" the South for secession with Reconstruction.

The Little Colonel is taken to a Northern hospital where he meets Elsie, who is working there as a nurse. The war ends and Abraham Lincoln is assassinated at Ford's Theater, allowing Austin Stoneman and other radical congressmen to "punish" the South for secession with Reconstruction.Part 2 begins to depict Reconstruction. Stoneman and his mulatto protege, Silas Lynch, go to South Carolina to personally observe their agenda of empowering Southern blacks via election fraud. Meanwhile, Ben, inspired by observing white children pretending to be ghosts to scare off black children, devises a plan to reverse perceived powerlessness of Southern whites by forming the Ku Klux Klan, although his membership in the group angers Elsie.

Then Gus, a murderous former slave with designs on white women, crudely proposes to marry Flora. She flees into the forest, pursued by Gus. Trapped on a precipice, Flora leaps to her death to avoid letting herself be raped. In response, the Klan hunts Gus, lynches him, and leaves his corpse on Lieutenant Governor Silas Lynch's doorstep. In retaliation, Lynch orders a crackdown on the Klan. The Camerons flee from the black militia and hide out in a small hut, home to two former Union soldiers, who agree to assist their former Southern foes in defending their "Aryan birthright," according to the caption.

Meanwhile, with Austin Stoneman gone, Lynch tries to force Elsie to marry him. Disguised Klansmen discover her situation and leave to get reinforcements. The Klan, now at full strength, rides to her rescue and takes the opportunity to evict all of the blacks.

Simultaneously, Lynch's militia surrounds and attacks the hut where the Camerons are hiding, but the Klan saves them just in time.

Victorious, the Klansmen celebrate in the streets, and the film cuts to the next election where the Klan successfully disenfranchises black voters. The film concludes with a double honeymoon of Phil Stoneman with Margaret Cameron and Ben Cameron with Elsie Stoneman. The final frame shows masses oppressed by a mythical god of war suddenly finding themselves at peace under the image of Christ. The final title rhetorically asks: "Dare we dream of a golden day when the bestial War shall rule no more. But instead-the gentle Prince in the Hall of Brotherly Love in the City of Peace."

The film was based on Thomas Dixon's novels The Clansman and The Leopard's Spots. At its Los Angeles premiere in February at Clune's Auditorium it was entitled The Clansman, but on the advice of author Thomas W. Dixon was retitled for its official East Coast premiere at the Liberty Theater in New York's Times Square three weeks later (March 3).

The title was changed from The Clansman to The Birth of a Nation to reflect Griffith's belief that before the American Civil War, the United States was a loose coalition of states antagonistic toward each other, and that the Northern victory over the breakaway states in the South finally bound the states under one national authority.

Production

Griffith agreed to pay Thomas Dixon $10,000 for the rights to his play The Clansman, but ran out of money and could only afford $2,500 of the original option. For the balance, he offered Dixon 25% interest in the picture. Dixon reluctantly agreed, but the film's unprecedented success made him rich: at the time, Dixon's proceeds were the largest sum any author received for a motion picture story, amounting to several million dollars.

Griffith's budget started at US$40,000, but the film ultimately cost $110,000 (the equivalent of $2.2 million in 2007). As a result, Griffith constantly had to seek new sources of capital for his film. A ticket to the film cost a record $2 (the equivalent of $40 in 2007). However, it remained the most profitable film of all time until it was dethroned by Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937.

West Point engineers provided technical advice on the Civil War battle scenes and provided Griffith with the masses of artillery used in the film.

The film premiered on February 8, 1915, at Clune's Auditorium in downtown Los Angeles.

Racism

Political ideology

The film is controversial due to its interpretation of history. University of Houston film historian Steven Mintz summarises its message as follows: Reconstruction was a disaster, blacks could never be integrated into white society as equals, and that the violent actions of the Ku Klux Klan were justified to reestablish honest government. The film suggests that the Ku Klux Klan restored order to the post-war South, which is depicted as endangered by uncontrollable blacks and their allies (abolitionists, mulattos and carpetbagging Republican politicians from the North). This was the dominant view among white American historians of the day, chief among them the Dunning School, but it was vigorously disputed by W.E.B. Du Bois and other black historians of that era, all of whom the Dunning School ignored. Some historians maintained this viewpoint even after World War II, such as E. Merton Coulter's in his The South Under Reconstruction (1947), and it took the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s for a new generation of historians (such as Eric Foner) to rethink Reconstruction and other ideas of the period.

Many elements of the film seem astonishingly racist to modern audiences. Black men are shown leering after white women, and black legislators are shown eating chicken and taking off their shoes in session. Although the film made use of some black actors in minor roles, most of the black and mixed race characters are played by Caucasian actors in blackface. This was the prevailing Hollywood custom at the time, as any actor who was to come in contact with a white actress had to be played by a white male (for example, the Camerons' maid is both white and obviously male).

In one intertitle, it proclaims that the following scene was based on an actual photograph of the state house, but the intertitle, in fact, cuts to an empty courthouse, then dissolves in to show the antics attributed to the blacks. This has been argued as Griffith covering his tracks, having based the scene on a photograph of the unoccupied courthouse and then misdirecting the viewer with the way the comment is written.

Responses

Though lucrative, and popular among some white movie critics and white moviegoers, the film drew significant protest from blacks upon its release. Premieres of the film were widely protested by the newly founded National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Griffith said he was surprised by the harsh criticism.

The film's politics made Birth of a Nation divisive when it was released. Riots broke out in Boston, Philadelphia and other major cities, and the film was denied release in Chicago, Ohio, Denver, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Kansas City, and Minneapolis. It was said to create an atmosphere that encouraged gangs of whites to attack blacks. In Lafayette, Indiana, a white man killed a black teenager after seeing the movie.

Thomas Dixon, author of the source play The Clansman, was a former classmate of President Wilson. Dixon arranged a screening at the White House, for the President, members of his cabinet, and their families. Wilson was reported to have commented of the film that "it is like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true." In Wilson: The New Freedom, Arthur Link quotes Wilson's aide, Joseph Tumulty, who denied Wilson said this and also claims that "the President was entirely unaware of the nature of the play before it was presented and at no time has expressed his approbation of it." The source for the false quote, often repeated in print, was apparently Dixon himself, who was relentless in his publicizing of the film; he went so far as to promote it as "federally endorsed". However, after controversy over the film had grown Wilson wrote that he disapproved of the "unfortunate production".

Several independent black filmmakers released director Emmett J. Scott's The Birth of a Race (1919) in response to The Birth of a Nation. The film that portrayed a positive image of blacks was panned by white critics but well-received by black critics and moviegoers attending segregated theaters. Likewise director/producer/writer Oscar Micheaux released Within Our Gates (1919) in response to The Birth of a Nation, and reversed a key scene of Griffith's film by representing a black woman assaulted by a lecherous white man.

The Birth of a Nation has been linked to the second emergence of the Ku Klux Klan, which was revived the year of the film's release after a period of non-existence, and to changing Northern public opinion toward the South. Despite the passage of 50 years, a strong pro-Confederate idealism remained in the South and impeded national ideological reunification. The Klan was using the film as a recruitment tool as late as the 1970s.

Nearly a century later, the film remains controversial. On February 22, 2000, in an article entitled "A Painful Present as Historians Confront a Nation's Bloody Past", staff writer Claudia Kolker wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “The end of World War I brought both economic crisis, and an anti-Red fever that extended to minority groups and trade unions. Just three years earlier, a defunct Ku Klux Klan leaped back to life with help from the film Birth of a Nation.”

Significance in film history

The film was released in 1915 and has been credited with securing the future of feature length films (any film over 60 minutes in length) as well as solidifying the language of cinema.

In its day, it was the highest grossing film, taking in more than $10 million at the box office according to the box cover of the Shepard version of the DVD currently available (equivalent to $200 million in 2007).

In 1992 the United States Library of Congress deemed it "culturally significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Despite its controversial story, the film continues to get praise from film critics such as Roger Ebert, who said: "The Birth of a Nation is not a bad film because it argues for evil. Like Riefenstahl’s The Triumph of the Will, it is a great film that argues for evil. To understand how it does so is to learn a great deal about film, and even something about evil."

In contrast, film historian Jonathan Lapper contends that it should no longer be considered a great film. In his article "The Myth of a Nation" he writes that "most critics (have) developed a pattern of response to the film that continues to this day: Praise the film's techniques, deplore the film's content, let technique trump content, declare the film a masterpiece." He argues that it is disingenuous to separate the film's content from its technique.

The website for Oldham County, Kentucky lists D.W. Griffith as a notable citizen and this film as his greatest achievement.

From Wikipedia

Very good!

ReplyDelete